- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

Zoldano: Beautiful Valley in the Eastern Dolomites, Among Rock Giants and Extensive Woodlands.

Longarone and Codissago

The sub-region of Zoldano covers in its entirety the valley of the Maè, one of the main tributaries of the Piave, into which it flows at Longarone – the town dramatically destroyed by the tragedy that struck on the night of 9th October, 1963, when nearly 2,000 lives were claimed by a massive wave precipitated from the overhanging Vajont dam).

The reconstruction of the town, despite having brought about an increased level of well-being over the years – as a result of the national subsidies for the rebuilding programme – could nevertheless not heal the wound left by the tragic events, and its brutal ugliness is still right in your face.

The only building that stands out in this architectural wasteland is the Parrocchiale (main church), built after a project by the renowned Italian architect Giovanni Michelucci between 1966-76 – a masterpiece that with its ascending, spiraling forms is as much a reminder of the destructive power of water as well as a cultured reference to the community-jelling function of architecture in ancient Greece.

Besides being a place of worship, the traditional shapes of a classical amphitheatre on the roof turn the building into a lay space of representation and remembrance (the association with Greek tragedy thus becoming particularly apt).

From there, the ancient murazzi are also visible above town: these are terraced walls which were built in the 18th century with the aim of protecting the surrounding orchards, and thanks to their elevated location they survived the tragedy.

In the town centre, right by the tourist office, a small museum is dedicated to the documentation of what happened on the night of October 9th, 1963 – and after such ominous events, it may seem perhaps somewhat paradoxical that today Longarone is one of the main industrial hubs of the province, hosting its most important exhibition centre.

The town is therefore not a particularly attractive destination for the nature lover, if not as a starting point of the Alta Via (Alpine Highway) No. 3 – so-called of the Chamois (Alta via dei Camosci), as it runs on trails once used by hunters – or for exploring either the Vajont valley to one side, or the Zoldano region (also known as Val di Zoldo) on the other – which is what we are going to do now.

But before we do that, let us just mention in passing that on the right bank of the river, in Codissago (part of Castellavazzo municipality, affected by the 1963 tragedy too) a small Ethnographic Museum documents another important traditional trade of old times: the flotation of timber, when the latter had to be transported from the woodlands of Zoldano and Cadore towards Venice by a skilled workforce (known as ‘zattieri’ – from the Italian word ‘zattera’, raft).

This industry – which harnessed the natural power of flowing water – needed several intermediate working stations along the way, one of which was here. These ports were the main – and often the only – source of income for the communities along the river, and when the activities connected with timber stopped, many villages fell into an almost irreversible decline.

But in the vicinity of Longarone – unbeknown to most – there are in fact also a few places of natural beauty, such as the Cajada Basin (‘Conca di Cajada’) and the ‘Val del Grisol’, or Grisol valley, of which a short description follows (it is described in more detail elsewhere; click link above).

The Val del Grisol (Grisol Valley)

An ancient forest, rich in treasure troves and filled with rare wonderful creatures: we are not talking about Harry Potter’s Forbidden Forest, though. This is the Val del Grisolforest — one of a kind in Europe for its many types of trees: an ancient and extraordinary forest, just like the “Old Woods” told of by Dino Buzzati in his stories.

The Val del Grisol originated from the confluence of a number of small valleys furrowing the eastern slopes of the Schiara-Talvena group (Val dei Ross, Val Costa dei Nass, Val Grave di San Marco); it is an isolated and solitary valley, dug into Jurassic marine sedimentary rocks (flinty Dolomite rocks; marls and limestone). Steep slopes and high rocky drops characterize the outcropping areas of the compact formations, while gentler slopes can be found only on the degradable marly formations.

Among the most notable valleys of the Park, the Val del Grisol differs from the others for the distinctive features of its wet, cool and shadowy ravine environments, and for the quality of its Silver Fir (Abies alba) and Beech woodlands (Fagus sylvatica). Silver Fir dominates between 600 and 1,100 meters of altitude, where it is particularly luxuriant and associated in a characteristic way with the so-called ‘noble’ broadleaved tree species such as Common Ash (Fraxinus excelsior), Sycamore Maple (Acer pseudoplatanus), Norway Maple (Acer platanoides), Wych Elm (Ulmus glabra) and Small-leaved Lime (Tilia cordata).

Among the most interesting floral species, Spindle (Euonymus latifolius) and Honesty (Lunaria rediviva) are worth a mention. This forest has exceptional features, and it is unique for its type in Europe; moreover, the Silver Fir woodlands of the Val del Grisol are one of the most extraordinarily rich wildlife habitats of the Park, displaying bird species such as Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis), Hazel Grouse (Tetrastes bonasia), Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix), Tengmalm’s Owl (Aegolius funereus), Black Woodpecker (Dryocopus martius), European Pine Marten (Martes martes), plus — among the mammals — Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) and Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus).

Forno di Zoldo and the Lower Maè Valley

The Grisol valley can be accessed some distance after entering the valley of the river Maè – whose lower reaches are narrow, and therefore historically very little inhabited – by the hamlet of Igne (which incidentally gives its name to an important geologic formation, mentioned above).

As it is indeed the case for most lower valleys in this area – locally known as canali, gorges – the Maè crosses a long canyon (Canale di Zoldo) before opening up into the wide basin where sits Forno di Zoldo, the main town of the Zoldano sub-region.

Its name suggests that this was an important mining centre (Forno, in this case, stands for ‘kiln’), where raw minerals (iron, lead and zinc) mined in the upper valleys of the Zoldano were gathered, sorted and partially worked before continuing their journey southwards towards Venice.

Forno di Zoldo, as it is the main centre of the valley, contains some notable buildings, the most representative of which is currently hosting the Museo del Chiodo (the “Nail’s Museum”; see image below), documenting the historical activities connected with iron mining in the area – but the most compelling sights are probably out of town (as it is generally the case).

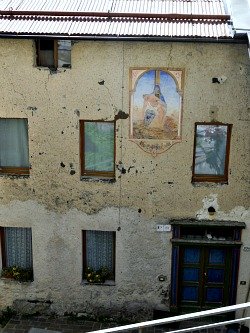

The municipality of Forno is composed of several small villages, some of which display interesting examples of vernacular architecture, as usual with local variations. This is especially true of the more outlying and elevated hamlets – such as Bragarezza and Astragàl – but perhaps none other is as interesting as Fornesighe, which is one of the most representative locations to visit, on that respect, in the whole province of Belluno.

Its tightly-knit group of multi-family housing units (a type of dwelling known as ‘multifuoco’), some dating as far back as the 17th century, is unique in the Eastern Alps: wandering the tiny alleyways – where house roofs nearly touch one another – makes for an atmospheric account of how life must have been here until not so long ago, unchanged for centuries. Fornesighe, perhaps, is never as evocative as on a snowy winter evening, when the smell of wood fires fills the crisp cold air.

Continuing on the road past the village, one reaches Forcella Cibiana pass (1,530 m) – the starting point for the excursion to Monte Rite, after which one enters Cadore.

The Pieve of San Floriano and the “Altare delle Anime”

Going back to the centre of Forno di Zoldo itself now, the main church of San Floriano in Pieve signals that this was indeed the ‘mother church’ of the whole Zoldano sub-region – something which is reflected in the high standard of its works of art.

Of very ancient origins (10th century), its appearance is now mainly gothic, with the exterior completely covered in frescoes (on the façade there is a gigantic San Christopher), flanked by the slender bell tower.

The interior contains one of the masterpieces of sculptor Andrea Brustolon, from Belluno – the so-called “Altare delle Anime” (the ‘Soul’s Altar’, 1687), a poignant representation of death – and of life in the thereafter – in cirmolo pine wood.

In the town centre, the recently restored old rustic building that hosts a small museum dedicated to the traditional industry of nail production (already mentioned above), obviously linked with the local extraction of iron, reminds that this area was once crossed by the “Via del Ferro” – the ‘Iron Way’ – re-equipped today as a long-distance trail with plaques that aim to show the route traditionally followed by the raw material, on its way down from the mines to the comparatively low-lying working mills of Forno and elsewhere (more on this below).

The Malga Prampér

For the nature enthusiast, from Forno di Zoldo there is the possibility of a very rewarding excursion to Malga Prampér (1,540 m), within the Zoldano section of the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park.

This location is reached via a minor road that ascends a side valley among beautiful beech and conifer woods, with spectacular views on the Spiz de Mezzodì (2,240 m; described below), until one reaches Rifugio Malga Prampér (1,850 m), a mountain hut in an open setting surrounded by meadows with important marsh habitats nearby, notable for their blossoming of Alpine flora.

From there, along well-marked trails that cross interesting glacial and karst formations, one can reach Pian de Fontana. The northern slopes of Monte Tàlvena (2,542 m) are also notable for their rare flora. As usual, bear in mind that these are high-altitude trails that require experience and caution. Some more detailed information on this beautiful area follow.

The Val Prampér: General Presentation

The Val Prampér is a glacial valley (see an image above). Enclosed among the Dolomite rocks of the Spiz di Mezzodi (2,240 m) and the Cime di Moschesin, the Val Prampér departs from the head glacier of the Val Balanzola and continues towards the Zoldo valley bottom, taking the shape of a typical glacial valley within the Dolomites.

The steep and craggy sides that delimit it are joined to the wide valley floor through extensive detritus’ faults, partly stable and covered by conifer woodlands, but partly also still active and unstable (and this is reflected in the presence of scree and detritus). From the dark and wooded valley bottom, the stony, arid and unstable bed of the Prampér stream stands out, flanked by erosion, landslides and rock collapses that go to dangerously feed – during flood events – the material being transported downstream by the water.

A country road enters the valley, skirting some noteworthy habitats as it rises: a) Prà Toront: a flat, open area, undulated by the presence of small glacial hills (moraines and moraine embankments); b) the stony and shifting stream bed of the Prampér itself, in the vicinity of Pian de la Fopa, with an interesting view on a steep and unstable scree (“Giaron de la Fopa”); c) Pian Palui: another extensive pasture with damp fields and small peat-bogs, probably originated by the slumping of an ancient marsh, which was formed above a moraine embankment; d) Malga Pramper’s pastures, with sparse glaciers’ detritus (Dolomite blocks emerging from the surrounding fields) and the not-so-well kept remains of moraine embankments; e) a debris-flow, along the path for the Pramperet hut, just past Malga Prampér (see above); f) Prà della Vedova – an ample, flat pass, modeled in the soft and impermeable marly-limestone rocks of the San Cassiano Formation (damp fields with interesting Mesolithic finds); g) the ‘city of rocks’ (“città di sassi” in Italian) by the Pramperet hut – a ‘macereto’ dominated by the huge boulders of an ancient collapsed landslide (perhaps above a snow deposit too). Some of these features are described in more detail below.

The Val Prampér in More Detail

The Natural Environment. The Val Prampér is the main access to the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park from its northern side. It is a wide and open valley which has conserved – in its higher reaches – the typical glacial morphology, while in the middle section the erosion due to the presence of streams and the great quantity of solid detritus – despite causing some concern for the stability of the mountain sides – has created ever new environments: some of them quite fascinating in their own right, and highly ‘natural’ (such as the extensive scree known as ‘Giaron de la Fopa’), others on a smaller scale: this is the case – for instance – of some patches of White Alder formations with maple and ash, or of the drier habitats with Dwarf Mountain pine that colonize the wide scree and detritus’ conoids.

In the lowest section of the valley – near the confluence with the Maé stream, and before the steep escarpment – there are some natural meadows, amongst which the most relevant in absolute for its bio-geographic value is the peat bog at Prà Torond. On the contrary, in the highest section – at the valley head, in the area of Prà della Vedova and by the Rifugio Pramperét (1,857 m) – notable wet meadows also develop, with interesting blossoming of orchids and Eriophorum (Cotton Grass) species. Of noteworthy effect are the so-called “Larch formations with Tall Herbs”, displaying a lush development in the understory too. The presence of springs with the characteristic accompaniment of mosses also increases the naturalistic value of a valley in which the long permanence of snow does not hinder a magnificent display of blossoms in the summer season.

Vegetation, Botanic and Fauna Aspects. From a botanic and vegetation point of view, there are innumerable points of naturalistic interest in the Prampér valley, some of which are quite extraordinary. The most important ones are situated by a few biotopes – such as the peat bog at Prà Torond, the wetland at Pian dei Palui and the area of Prà della Vedova, by the Rifugio Pramperét. Among the most noteworthy aspects, one can include different forest types (mixed beech-spruce and larch formations; Dwarf Mountain pine formations), the progressive phases of colonization of meadows and pastures by woodland, White Alder formations along the streams and on the mountain slopes, and finally it is also interesting to observe how naturalistic forestry is carried out inside a protected area.

Among the fauna aspects that more deserve attention one must mention the numerous species of amphibians (such as Montane Frog, Common Toad and Yellow-bellied Toad); also, interesting species of reptiles can be observed here (like the European Viper – as well as the Viviparous Lizard, which is quite abundant); rare species of bird, such as Goshawk, Sparrow-hawk, Black Partridge, Capercaille, Tengmalm’s Owl, Tawny Owl, Black Woodpecker, Great-spotted Woodpecker and a particularly abundant community of passerines can also be spotted; several mammals like deer, roe-deer, chamois and marten are present in the area too; among the micro-mammals, particularly, Field Vole (Microtus agrestis) stands out for its zoo-geographic interest.

The Main Itinerary from Zoldano to the Pramperét Hut (Rifugio Pramperét). Once crossed the bridge over the Maé on the road to Pralongo, there immediately starts – by a hairpin bend – the single lane track that enters the Val Prampér. After a short and steep rise of about half a km, one reaches the area of Prà Torond, where the interesting peat bog described above is situated. From there it is possible to connect – through existing paths, lanes and tracks – both with Pralongo and the locality of Baròn (see below). The road now continues on almost flat ground, or with gentle rises, until Casera Castelàz (996 m), where a small area has been equipped by the Park authority; from there, a steep path takes to Casera del Mezzodì (Rifugio Sora el Sass), while an easy track goes downhill back to Baròn. The trail that continues uphill leads into the heart of the Val Prampér, gaining altitude all the while.

After passing the artificial basin built by the ENEL (the National Italian Electricity Company) one reaches Pian de la Fopa (1,150 m), where a second area equipped by the Park is located; from this point onwards, the road is not accessible to cars (but there is ample free parking). The itinerary continues, now flanking the course of the Pramper stream on flattish terrain, and reaching the boundary of the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park, from where – past the so-called Acqua della Madonna and some hairpin bends – begins the rise to Pian dei Palui. These uplands are the interesting site of ancient pastures, rich in wetlands; once this area is left behind, one can continue towards Malga Prampér (see above), where the road terminates. The itinerary now doubles the route of CAI trail marked no. 523, which – in just over an hour – leads on to Rif. Pramperét (1,857 m). Besides the forest and meadow habitats encountered along the trail, among the most noteworthy aspects of this itinerary one certainly has to include the panoramic views towards Monte Puma, the mountain groups of Cima Coro and Cima Venier; the Spiz di Mezzodì (described below); the Castello di Moschesin; the Cime della Gardesana and Petorgnòn; the Cime di Pramper – and, towering above them all, the majestic Pelmo.

Shorter Routes. In order to facilitate a network of shorter circular itineraries – especially in the lower section of the valley, as well as on the Zoldano valley floor – a few alternative routes have been individuated; all of them follow existing paths and roads, and can be particularly appealing to those who do not wish to venture high up in altitude.

A first itinerary has been devised in order to reach the area of Prà Torond. Walking up from the locality of Baròn, once left the last few houses behind, the ascent starts along a very steep path that allows one to gain altitude quite rapidly, until reaching the flattish area of Prà Torond, from where the itinerary continues on existing paths, also making use, partly, of the cross-country ski route (used as such only in winter), until reaching shortly after the road of the Val Pramper, which comes up from the main Zoldano valley floor.

A second, important itinerary connects the area of Prà Torond to Pralongo; it also uses existing forestry tracks that allow one to create circular routes; the one being currently described was already frequented in the past, but today is not very well marked. To sum up, the itineraries in the Val Pramper – intended as a whole – can easily be walked either entirely or partially; in particular, the following can be suggested: link Baròn – Pralongo – Prà Torond on foot; Casera Castelàz – Pian de la Fopa by car; Pian de la Fopa – Rifugio Pramperét on foot.

Spiz di Mezzodì: a Small Dolomite Chain

“Now Bàrnabo sees the mountains. They do not really resemble towers, or castles, nor ruined churches, but only themselves, just as they are, with their white landslides, the gravelly ledges, the never-ending edges, a precipice folded in the void”.

This is how local writer Dino Buzzati described the mountains he loved so much in a famous novel, "Bàrnabo delle Montagne" ('Bàrnabo of the Mountains').

At the northern edge of the park, to the north of the Valsugana fault-line, the val Prampér (just described above) is enclosed by a circle of mountains of a typically Dolomite outlook.

To the hydrographic left, the turreted crags of the Castello di Moschesin mark the beginning of an amazing sequence of jagged peaks, surrounded by enormous screes which terminate at the Cime di San Sebastiano, while to the right a tormented ridge develops from the Prampér across a carousel of peaks and passes, towers and deeply incised cuts to terminate by the group with the very indicative name of ‘Spiz’ ('point' in the local patois).

Faced with a substantially uniform lithology, with walls of Main Dolomite superimposed on to eroded layers of the San Cassiano and Raibl Formations, the landscape here is in fact quite articulated, as if in response to a complex tectonic arrangement.

In particular, the Cime di Mezzodì (the Midday Peaks; 2,240 m) are mostly constituted of a cover that represents a doubling of two Main Dolomite layers. The over-thrust is witnessed by the presence of the Raibl Formation between two types of Dolomite to the south of Casera Sora’l Sass (1,600 metres) and a vast discordant surface between the Main Dolomite layers at Cima del Coro (2,100 metres).

The sub-horizontal Main Dolomite layers are further fractured by other faults in different directions. The actual Val Prampér has developed along a fault-line that has lowered the summit of Monte Prampér of about 200 metres from the surrounding peaks – such as the Cime di Gardesana. Another over-thrust can be recognized where the Main Dolomite meets and immerges under the Raibl Formation layers, which surface at the base of the Spiz di Moschesin.

On the stair-like (‘a gradoni’) structure of the Castello di Moschesin one can indeed observe and individuate other faults and fractures that become even more frequent in the Tamer group.

This intense tectonic activity has had visible consequences over the landscape, which is finely articulated with needles, pinnacles, passes and rock canals (or scree; canaloni in Italian), highlighting the freezing/thawing cycles, with the subsequent formation of enormous detritus’ faults, which facilitated the infiltration of water into the main body of rock – that is so often the cause at the origin of huge landslides.

Zoppè di Cadore and the Pelmo

Another deviation from Forno di Zoldo climbs up the short Rutòrto (literally, ‘Crooked brook’) valley, and after a steep rise leads to the tiny hamlet of Zoppè di Cadore – an isolated appendix of Cadore over the Boite watershed (as indeed is Selva di Cadore, in the upper Fiorentina valley – see below) known as ‘Oltremonti’, which has historically always gravitated on the Zoldano.

Zoppè is the less inhabited and most elevated municipality in the province of Belluno, and it is dominated by the massive dome of Monte Pelmo (3,168 m), which here crowns the skyline in all of its majestic glory.

Zoppè also has many interesting examples of vernacular architecture (see an image below), plus – in the church of Sant’Anna – a beautiful painting (Madonna and Saints) allegedly attributed for many centuries to the Great Master Titian (further studies, however, seem to have ascertained that this is not the case, but it was probably executed by a very skilled painter belonging to the Titian’s circle – perhaps Francesco Vecellio – hence the difficulty in the attribution).

Steep walks lead up from Zoppè along the Pelmo slopes to Forcella Candolada, from where a long haul can take you all the way down to Vòdo in the Boite Valley; for more informations about hikes and treks from Zoppè di Cadore, refer to the dedicated page.

Zoldo Alto and the Upper Maé Valley

The upper section of the Maé valley leads to Zoldo Alto, a locality that – despite being historically connected with the mining industry (the toponym of Fusine again indicates the presence of kilns) – is today mainly geared towards winter tourism, given the proximity of imposing Monte Civetta (3,220 m).

In Zoldo Alto, old vernacular houses can be admired in the hamlets of Costa, Brusadàz and Coi, while the church of S. Nicolò also contains works by 17th century sculptor Andrea Brustolon.

A deviation allows to reach Chiesa di Gòima, in a side valley that was also heavily exploited in the past by the proto-industrial mining industry, documented in the local, small Ethnographic Museum of Valle di Gòima, where materials referred to agriculture and cattle farming are also on display.

The “Vie del Ferro” (“Iron Ways”)

The Alps of Veneto were once zig-zagged by a great number of specialized trails; each of them followed a different route according to the specific needs for which it had been traced in the first place. In the same area one would therefore find valley floor trails alongside half-way routes (a mezza costa in Italian); ridge ways and transversal routes towards the passes connecting the valley floors to high-altitude pastures. More trails linked villages and communities among themselves; others still were commercially oriented, or used by shepherds, hunters and smugglers; passing troops also transited, but one of the most important uses was for transportation of the raw material obtained from either woodland or mines.

Each of these uses had its importance at different times in history, and for longer or shorter periods. The so-called “Vie del Ferro” (“Iron Ways” – not to be confused with the ‘vie ferrate’, equipped trails for mountaineering) develop in NE Italy from the 12th century onwards, both for connecting different mines amongst themselves and with the kilns, and for allowing transportation of the raw material (as well as the finished products) towards the valley floors and – later on – also to the town and cities on the Venetian plain.

The first to make use of the iron mines and kilns were local people from Cadore and Zoldano; they were followed, and sometimes substituted – especially during the course of the 16th century – by entrepreneurs from Belluno but also, as the mainland started to exert more influence, from further away (Treviso, Venezia). Beginning with the second half of the 15th century, the kilns (‘forni’) of the Zoldano (and also of Cadore) were being almost exclusively fed with the mineral that came from the important Fursìl mine, at the border between Colle Santa Lucia and Cadore; the mining industry – so vital for this part of the Venetian mountains – then gradually died down (depending on the different areas) between the 17th and 18th centuries.

The itineraries proposed within the context of the “Vie del Ferro” initiative have all been conceived for a full fruition of the multifold aspects in which this territory now presents itself: historical evidence, linked to the different artifacts (permanent and temporary dwellings; religious buildings; factories and workshops connected with mining or with the transformation of the raw materials; museums), is in turn strictly interwoven with the history of the landscape, which is characterized by the natural and environmental aspects (described above) peculiar to the Zoldano, which is a typically transitional area between the Pre-alpine and the proper Alpine (Dolomite) regions.

Selva di Cadore and the Val Fiorentina

Past Zoldo Alto, the National road climbs up the slopes towards Forcella Staulanza (1,773 m): this is a magnificent route that – either side of the pass – runs among monumental, pristine conifer woods. The pass itself is dominated by the summit of Pelmetto (2,993 m), after which one descends into the Val Fiorentina towards Selva di Cadore.

This municipality – which, like Zoppè, belongs to the part of Cadore known as ‘Oltremonti’, as it lies beyond the Boite watershed – was also inhabited by a colony of miners.

The village gathers a good number of old, mostly wooden, vernacular houses, especially in the elevated hamlet of L'Andria, with an impressively long sequence of buildings, traditionally facing south to make the most of the sunlight (see an image below).

There are also two interesting churches: in Selva di Cadore itself is San Lorenzo (Saint Lawrence), which was first erected in the 13th century, then remodeled: it contains a cycle of 16th century frescoes by an unknown painter (perhaps Giovanni da Mel) and works of another painter from Cadore, Antonio Rosso. The church of Santa Fosca, in the hamlet of Pescùl – also gothic in appearance – has a gigantic depiction of Saint Christopher on the façade.

The Civic Museum, of geologic and archaeological interest, displays the findings of the so-called “Uomo di Mondeval” (‘Mondeval’s Man’): a lesser version of the iceman Ötzi that came to light from a Mesolithic site up nearby Passo di Giau; the remains are believed to be those of a hunter who was buried about 7,400 years ago. There is also an historic section that documents the mining past of the community, as well as geologic evidence of the dinosaurs’ footsteps at nearby Monte Pelmetto.

Climbing further up in altitude from Selva, one can reach the aforementioned Passo di Giau, 2,233 m, connecting the area with Cortina d'Ampezzo and an ideal starting point for hikes on the Croda da Lago (2,701 m) or to the impressive rocky outcrop of the Cinque Torri (the ‘Five Towers’), at the foot of the Averau (2,647 m) and Nuvolau (2,574 m) groups, both belonging to the Ampezzo Dolomites.

Return from Zoldano to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2012 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.