- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

Cortina: the Spectacular Setting of the “Pearl of the Dolomites”.

Cortina: a Celebrated Name in the History of Mountaneering

Cortina d’Ampezzo is certainly the most renowned destination of the province of Belluno, known as the “Pearl of the Dolomites”, as well as being one of the major resorts in the Alps.

It owes its status, most notably, to its geographical location at the head of the Boite valley, where an undulated basin, surrounded on all sides by majestic Dolomitic peaks – the Conca di Cortina (aka Conca Ampezzana; Cortina basin) – opens up at an average altitude of 1,200 metres (below, a view with Mt. Pomagagnòn, 2,664 m, in the background).

The location is what decreed the destiny

of Cortina in the first place, since the town is

surrounded on all sides by some of the most celebrated peaks of the Dolomites, such as (starting from the nearest) the Pomagagnon, Cristallo, Sorapiss, Antelao, Croda da Lago, the Averau/Nuvolau group, the Cinque Torri and finally the Tofane, and – partly concealed by the latter – the Lagazuoi.

This unique location started to attract – since the latter part of the 19th century – the first tourists, at that stage, in fact, an elite of alpinists. The first pioneers arrived especially from England, Germany and Austria (one has to bear in mind that Cortina – at the time still known with the ancient name of Ampezzo – was still part of the Austrian Empire).

Their intention was to climb (as a matter of fact, ‘conquer’) the Dolomites’ summits, – at that stage still virtually untouched by man – following on the footsteps of Paul Grohmann, the famous Austrian mountaineer who in 1864 had made the first ascent to the Marmolada, the Dolomites’ highest mountain. His guides were from Ampezzo, and that contributed to make Cortina's reputation known far and wide in the mountaineering elite.

In fact, all the Dolomite mountains surrounding the ‘Conca d’Ampezzo’ were climbed one by one in what are still remembered to this day as momentous expeditions, and this called for more and more attention: visitors started to flock to Cortina in big numbers, and its fame increased; as a result, more and more hotels were built, and its name was established, rapidly turning the place from a sleepy agricultural community into a thriving mountain resort.

Ampezzo only became Italian again in 1923 (it had been lost by Venice to the troops of Maximilian of Austria as far back as 1511), and only at that point was its name officially changed to Cortina d’Ampezzo.

This was a delicate time following the First World War, and at the onset of the Fascist period, Mussolini invested a lot in the resort, probably as part of a propaganda designed to launch it, at that point, as a First Class “Italian mountain winter resort”. In fact, he proved successful at this: the first cable cars and ski slopes were all opened up in those years – and that marked the beginning of snow-sports tourism.

But it wasn’t until well after World War II that Cortina really took off in earnest as a major mass-tourism destination; the biggest boost came from the Winter Olympics of 1956, which meant a lot in terms of new infrastructures being built – specifically directed, as can be imagined, at winter sports – such as the impressive Stadio del Ghiaccio (Ice-rink), accompanied by many new hotels and second homes.

Despite that boom, though, Cortina did manage to remain true to itself, retaining an aristocratic air, and not losing touch with the ‘elitist’ feel that had decreed its fortunes in the first place.

Perhaps, this is due to the characteristic identity of the people of Ampezzo, which consider themselves distinct from the surrounding areas, and so have always retained aspects of proud independence.

This is reflected in the local Ladin language (called ‘Ampezzano’, while the area can be considered part of the so-called Ladinia Veneta), but also in the presence of institutions which govern the management of woodland and of other natural resources (namely the ‘Regole’ – more on this below), following strict rules.

Therefore, despite Cortina’s appearance as a relatively big town, successive administrations have provided a continuity in containing the excessive spread of second homes, while forbidding, at the same time, the erection of tall, disproportionate buildings (a plague in so many other resorts of the Alps).

To this day, therefore, despite being massively frequented, Cortina remains, in my view, a beautiful place to come to – especially as it is so multi-faceted.

Crowds can be a problem, but they can also be easily avoided – especially if you refrain from the traditional afternoon stroll and shopping frenzy along Corso Italia, as popular in summer as well in the winter season (below, an image of the Campanile, with the Tofana di Rozes in the background).

Cortina: Majestic Peaks and Fantastic Nature All Year Round

In fact, it is easy to leave civilization quickly behind as paths wind their way into the mountains – and once you’re out there, you'll have so much choice that you’ll rarely have to contend with overcrowding.

The only exception is perhaps the first three weeks of August, when the majority of Italians still take their holidays, and that – especially around the main Rifugi (mountain huts) – can be a very busy time indeed. But for the rest of the time, it is not difficult to find tranquillity – and the much quieter September is perhaps the best month in the whole year for rambling across the Dolomites.

Any direction you may go, there is an extensive network of trails awaiting to lead you into dense coniferous woodland, replaced at higher altitudes by open meadows that host the most notable habitats if you’re interested in the Alpine flora.

Higher still, an abundance of Alpine huts pepper the high reaches of this section of the Dolomites, allowing you – should you wish to – to plan long-haul treks in altitude (below, a picture of the Cinque Torri – the magical Five Towers).

The mountains just north of Cortina, especially, offer stunning panoramas, and particularly noteworthy is the Regional Natural Park of the Ampezzo Dolomites (“Parco Regionale delle Dolomites d’Ampezzo”) that shares its borders with another Park, this one belonging to South Tyrol (the “Fanes-Sennes-Braies”); together, these two reserves form one of the widest expanses of uninhabited territory in the whole Dolomites’ region.

Here, you may find long, interesting walks – such as on the Fanes plateau, which is one of Italy’s finest tracts of limestone scenery. In particular around the Croda Rossa/Rotwand (3,146 metres), the Conturines and Picco di Vallandro, paths can be some of the Dolomites’ loveliest and least travelled, and the Alta Via (Alpine Highway) No. 1 also crosses the area.

If you belong to the category of the less energetic hikers, the old military tracks are particularly good, as they usually ascend the slopes with a less steep gradient.

The summit of peaks, also, unlike many others in the Dolomites, are generally speaking more accessible to the average walker, partly because of the extensive network of paths and “vie ferrate” (literally, iron ways) – even though you’ll need to be fitter (and well-equipped) for these.

The "Alta Via" No. 4 and No. 5 also cross the area just east of Cortina, in the section that leads towards the Tre Cime di Lavaredo/Drei Zinnen and further into the Dolomiti di Sesto/Sextnerdolomiten – also a Natural Park belonging to South Tyrol.

The Dolomiti d’Ampezzo Natural Regional Park

The Dolomiti d’Ampezzo Natural Regional Park was established in 1990, and it covers 11,200 hectares in the heart of the eastern Dolomites, on the border between Veneto and Alto Adige/Suedtirol (South Tyrol).

It is ruled under the ancient and joint ownership of the so-called Regole d’Ampezzo, and its territory falls entirely within the municipality of Cortina.

The Regole are old associations, created by the local families, whose aim is to govern the collective use of pastures and forests; their establishment dates back to the period of the first permanent settlements in the Ampezzo valley, at the time of Celtic and Roman colonization – therefore they are very ancient, and the attachment of the ampezzani to this dignified institution can be easily understood.

The Regole have now been recognized also by the Italian State and by the Region; they are at the historical and cultural foundations of this area, and the Park has been created with their approval precisely in order to preserve the unique environmental heritage of the Ampezzo Dolomites.

The protected area is wedge-shaped, with two lateral branches that merge, to the north, with the neighboring Parco Regionale di Fanes-Sennes-Braies: together, the two reserves form a protected area with homogeneous environmental features, extending on the whole for 37,000 hectares.

The territories of the two parks are also quite homogeneous as far as the use of soil is concerned, since there are neither technological tourist infrastructures – such as Alpine ski slopes or chair-lifts – nor urbanized areas and villages. This makes for a clear distinction between the sections which are dedicated to forests and pasture, and those that are more exclusively devoted to conservation.

The protected area includes some very notable Dolomite mountains, such as the groups of the Tofane (3,244 m), Fanes, Croda Rossa d’Ampezzo, and Cristallo (3,221 m), divided respectively by the Travenanzes, Fanes, Boite, and Felizon valleys.

These valleys are narrow and enclosed by steep gorges in their lower sections, while they open up in wide plateaus at high altitudes (below, a view on the Tofane group from just outside Cortina by the hamlet of Campo).

As mentioned before, the highest peaks in the park are all around 3,200 m; amongst these, the Tofane and the Cristallo are renowned Dolomite mountains, characterized by high rocky walls which often reach the forests of the sub-alpine area.

The massifs of Fanes and Croda Rossa present instead less difference in height, and alternate wide karstic plateaus with high-mountain grasslands (below, the Croda Rossa displays incredible colours because of the iron dioxides present in the rock composition).

In the highest and more shady places of the northern slopes of the Tofane, Cime di Fanes and Cristallo, small cirque glaciers are still concealed, sometimes covered by a thick layer of detritus (scree).

These tiny glaciers are situated between 2,800 and 3,000 m of altitude, and even if they shrink every year – working almost as living thermometers of the climatic changes – they continue to be an integral part of the Park landscape, and to feed the summer water flow of the streams.

In fact, one of the most beautiful natural monuments within the Park consists of the waterfalls formed by the Fanes stream (Cascate del Rio Fanes), reaching the ravine of the Travenanzes valley; the falls develop in three successive jumps, each more than 50 m high, and given the great quantity of water flowing into them, they are roaring and particularly suggestive.

Given the strategic importance of these mountains – still today so close to the Austrian border – it should be no surprise to come across World War I battle debris, left over from the old 1915-18 front. Many walks (for example at Monte Piana, around the Tre Cime and, especially, in the Lagazuoi area) pass scenes of savage fighting, and around this latter area a striking Open-Air War Museum has been created, making hiking up here a particularly moving experience.

It seems almost impossible to compare the peaceful comings and goings of today’s walkers with the cruelties of war, at a time when soldiers here had to endure extremely harsh conditions, living for months in shelters buried deep down under many metres of snow.

Still today, it is a very humbling experience to be able to enter these tunnels and underground rooms, and be surrounded at the same time by this most stunning of environments.

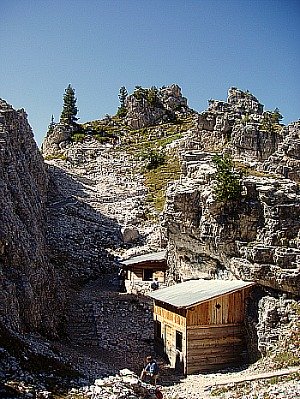

The nearby old Forte Tre Sassi at Sass de Stria (the “Witch’s Rock”, on the road to the Passo Valparola; 2,192 m), also, has been converted into a proper museum (pictured below, part of the Lagazuoi Open Air War Museum).

Cortina’s First-Class Cultural Life

Truth to be told, after spending so much time in nature, there is yet another aspect of Cortina that needs to be acknowledged, and it is the fact that it retains a good number of cultural institutions – unusually so, perhaps, for an Alpine town of these dimensions.

This aspect also owes a lot, again, to the pride of the local people, in their wish to retain their cultural identity: so there is a brand new headquarters for the Ethnographic Museum and the Rinaldo Zardini Geological Museum – with its extensive collection of minerals and fossils: both these institutions are now hosted in brand new buildings at Pontechiesa, just outside the pedestrian area – while in the town centre, right by the church, there is a small but very interesting Museum of Modern Art (the Pinacoteca Mario Rimoldi; pictured below, an image of the newly refurbished Ethnographic Museum, in the new headquarters at Pontechiesa).

Most of these museums were born out of the donations of local collectors to their hometown; a symbol, again, of faithfulness to one’s sense of belonging displayed by the people of Ampezzo, thus assuring a lineage of continuity in the cultural inheritance.

The main church (Chiesa parrocchiale), dedicated to the Santi Filippo and Giacomo, contains decorations by the Austrian painter Franz Anton Ziller and local 19th century artist Giuseppe Ghedina, which on the whole lend a Tyrolean feel to the building – especially so given the overall German Rococo style of the interior.

The so-called Madonna’s altar is a renowned work of sculptor Andrea Brustolon (1724), so that the art contained within this building is a real embodiment of Cortina’s double soul – Italian and Tyrolean.

The slender bell tower (Campanile) is a point of reference from anywhere around the ‘Conca d’Ampezzo’ , and is a landmark visible for miles (below, an image of the main church; the Mario Rimoldi Museum of Modern Art is located nearby).

The Vernacular Architecture of the ‘Conca d’Ampezzo’

This aspect is also expressed by the vernacular architecture of the ‘Conca d’Ampezzo’. In the many small hamlets that are scattered all around Cortina (32 in all – and what is now Cortina town centre was originally just one of them), beautiful examples of what is known today as “architettura ampezzana” (Architecture of Ampezzo) can still be admired.

These are wooden houses that were originally built in clusters and in such positions to make the most of the natural gradient and sunlight (the main facade is usually facing south).

Many of these houses have now been turned into classy second homes (with fascinating interiors you can only admire in books, unless you have a friend living in one of them!), but some have managed to retain their original character, with carvings on wood depicting the symbols of the owner’s family.

For a glimpse of these houses, it is best to head for the more peripheral hamlets of Cojana, Mortisa, Col, Chiave, Verocai, Lacedel and Chiamulera – all easy to identify on a map, and within perfect reach of the town centre on foot.

On a final note, then, one could say that Cortina is not only a glitzy, aristocratic winter resort, but that it also offers a variety of other motives of interest, which could easily be combined for a varied and soul-enriching experience on many levels.

Return from Cortina to Dolomites

Return from Cortina to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2019 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.