- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

Northern Apennines: Endless Mountains, Valleys and Woodlands for the Nature and Mountain Lover to Enjoy.

The Origin of the Apennines

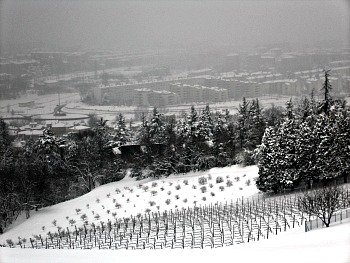

The Apennines are the central spine of Italy, and they can be roughly divided into a northern, central and southern section. The Northern Apennines are being dealt with in this page, whose purpose is to first give you a general description of the nature of this long mountain range, and then focus with more detail on its northern section, with the intent to direct the visitor to different points of interest within it (in the picture above, see a picture of the Northern Apennines taken from the Raticosa Pass, situated at the boundary between Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna).

The geology of the Apennines is quite complex, and this complexity engenders different landscapes. The lower reaches of the range are formed mainly of sand and silts, giving the mountains a softer, more rounded aspect, while the backbone of the chain is formed of harder rocks such as limestone and granite.

The Apennines were created by the so-called Apennine orogeny, the mountain-creation process which began around 20 million years ago – in the Neogene period – and continues up to today.

Geographically, they are or appear to be continuous with the Alps, but in fact they were generated by a separate process. Both the Alps and the Apennines are made primarily of sedimentary rocks, resulting from the materials deposited on the bottom of the Tethys sea during the Mesozoic era, but the Apennines were created in fact much later, and thus are not – as many believe – a displacement of the Alpine chain. Instead, they were separated by the Adriatic trench and were never a part of the same system, so that – however similar – the tectonics is still not the same as the one which created the Alps.

There are also notable differences between the two sides of the range: the eastern side of Italy features fold-mountains raised by compression forces acting under the Adriatic sea, while on the western side fault-block mountains prevail, created by a spread or an extension of the crust under the Tyrrhenian sea – so that the Apennines are unique in having mountains derived from both compression and extension.

Within the compression zone, sedimentation occurred at a much faster pace than subduction; in the extension zone, on the contrary, both the folded and the fault-block systems include parallel mountain chains. In this latter zone, the ridges are lower and more steep-sided, following the seams of the original faults.

The Geography of the Apennines

The Apennines consist of parallel smaller mountain chains, extending for 1,200 km along the whole length of peninsular Italy. This system forms an arc enclosing the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian sea to the west and the Adriatic sea to the east, thus dividing Italy into a Tyrrhenian and an Adriatic sector.

Most big cities of central-northern Italy lie either at the foothills of the Apennines (most notably Genoa, Florence and Bologna, plus most towns of Emilia-Romagna), or amid the outlying ranges: amongst the latter are Siena, Arezzo, Perugia, Terni – and many others.

Geographically, these outer sectors are not considered part of the Apennines proper but are termed Sub-Apennine or Anti-Apennine, and are mainly found in central/southern Italy. Rome itself lies further away along the Tiber valley – close to its outlet into the Tyrrhenian sea – but the Apennines are in sight from there too.

The Apennines include 21 peaks over 1,900 m (6,200 ft), which is the approximate tree line. This line can be found at around 1,900/2,000 m, so that only about 5% of the area covered by the Apennines is above it; the snow line is virtually at about 3,200 m (therefore no peak is above it). The number of plant species has been estimated at 5,599; 728 of which are contained within habitats above the tree line.

From a technical point of view, the Apennines start at Altare – at the so-called Colle di Cadibona – a low pass (only 436 m) situated at the border between Piedmont and Liguria, west of Genoa and inland from Savona.

The Northern Apennines then proceed eastwards, running in an arc covering most of inland Liguria, a small section of Lombardy (in the province of Pavia), and then the whole length of Emilia-Romagna – a very long region whose axis is the Via Emilia (in fact, the region derives its very name from this almost straight Roman road traced between Piacenza and Rimini, which connects all its main cities).

The Via Emilia divides Emilia-Romagna almost neatly into two parts: the extensive plains of the Po valley (or Val Padana) open up to the north, while the hilly, mountainous expanse of the Apennines lies to the south. Each province of Emilia-Romagna has its section of Apennines, which usually take their name from the main city of reference (for example, Appennino Parmense from Parma; Appennino Modenese from Modena; Appennino Bolognese from Bologna – and so forth).

To the Northern Apennines belongs also a section of Tuscany, covering roughly half of the region, and coinciding approximately with the mountainous parts of the provinces of Massa-Carrara and Lucca, where is also located the outlying range of the Alpi Apuane – and there is much debate as to whether the Apuane are part of the Apennines or not (as a matter of fact, the Apuane have a different geology, since they are formed of marble, but they are separated by the main system only by the Serchio valley). The provinces of Prato, Firenze and Arezzo also include a large section of the Northern Apennines within their territories.

Etymology of the Apennines

The most commonly accepted etymology of ‘Apennines’ derives their name from the Celtic root Pen(n) or Ben, meaning ‘summit’ or ‘peak’ – which allegedly has been assigned to them during the Celtic domination of Italy in the 4th century AD (but possibly even before).

This name, it seems, originally applied only to the Northern Apennines, and was extended at a later stage to include the whole range (but as late as in year 2000 the Italian Ministry of the Environment, following recommendations from the APE project – “Apennines Park of Europe” – included also the mountains of northern Sicily within the system, bringing the length of the whole range to 1,500 km; one could therefore say that the denomination remains alive and shifting to this very day).

It may add a note of interest to reflect on the fact that the same Celtic root lends its name to other mountain ranges in Europe (such as the Pennines in England), as well as to many single peaks or villages within the Apennine range itself (such as Monte Penna in Liguria, Monte Beni at the boundary between Tuscany and Emilia, or the towns of Pennabilli in Montefeltro and Penne in Abruzzo – just to mention a few examples).

Roughly speaking, the different parts of the Apennines are named after the region where they are located, but provincial and regional boundaries have not been stable over the years either, so sometimes this has resulted in discrepancies between the geographical borders (mainly identified with the watersheds) and the administrative ones.

The Northern Apennines in More Detail

Zooming in a bit more detail within the individual regions forming the Northern Apennines now, belonging to Liguria are the valleys of the Bormida, Tanaro and Scrivia rivers, and the beginning of those of the Trebbia and Taro too – two important rivers which further flow into Emilia; towards the southern end of the region, the Aveto Natural Regional Park includes Monte Penna. Liguria’s highest peak is Monte Maggiorasca (1,780 m).

The following section – covering Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany – is known as “Appennino Tosco-Emiliano” (or ‘Tuscan-Aemilian Apennines’): this starts roughly east of the axis formed by the Magra and Taro rivers, whose valleys are connected by the Passo della Cisa (1,041 m).

The elevations get higher in this part, with a succession of peaks such as – just to mention the main ones – Monte Cusna (2,121 m) in the province of Reggio Emilia (located in an area covered by the extensive Alto Appennino National Park); Monte Cimone in the province of Modena (at 2,165 m the highest point in the Northern Apennines) and Corno alle Scale (1,945 m), in the province of Bologna. These latter areas are all occupied by smaller but interesting Regional Parks (the picture below shows Monte Cimone as seen from the town of Monghidoro, in the Bologna Apennines).

From a geographical point of view, the Northern Apennines end at the source of the river Tiber on Monte Fumaiolo (1,407 m), where the borders of three different regions converge (Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany and the Marche). This point marks the beginning of the Central Apennines further south, while the area is also covered by an extensive and very important National Park with a long name – the Parco Nazionale Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona and Campigna.

Since 1865 onwards a series of tunnels has perforated the middle section of the Northern Apennines in order to improve communications between the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic sides of the country, as well as connecting Northern and Central Italy. But the Romans were the first to trace a number of roads through the Apennines – the most famous to this day being perhaps the via Flaminia, running between Rimini and Rome.

The Futa pass (Passo della Futa) also lies on a Roman road (the “via Flaminia Minor”), while the road bearing the same name (“Strada della Futa”) is a Napoleonic feat of engineering dating from the early 19th century; a time when several different roads were traced between Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany (as for example the via Vandelli between Modena and Massa, or the via Giardini between Modena and Lucca).

Over time, however, the interest focused on connecting the two regional capitals, Florence and Bologna – the Futa Road representing the first effort in that respect. With the advent of the railway (the so-called ‘Direttissima’, which dates from 1934) – and even more so with motorway traffic – the doubling of tunnels amplified relentlessly, so that the axis Bologna/Florence was turned into the most congested section of the Apennines; nevertheless, some interesting sights surprisingly remain, even not too far away from this busy crossing link (as for example Monte Beni).

The terrain of the Apennines (as well as that of the Alps) is to a large degree unstable due to various types of falls and slides of rocks and debris, earth- and mud-flows, lateral spreads and sink holes. These phenomena are so widespread and problematic that an Italian government agency (founded in 2008) published in that year a special report: the Italian Landslide Inventory – an extensive survey of all the historical landslides in Italy.

The most unstable terrains in the Apennines are deemed to be those on the eastern flanks of the range (in the Tuscan-Aemilian section), in the Central Apennines and on the eastern side of the Southern Apennines. The Apennines are gradually slumping away to the north-east into the Po Valley and the Adriatic fore-deep; that is, the zone where the Adriatic floor is still being subducted under Italy.

Walking in the Apennines

A number of long hiking trails wind their way through the Apennines: one is the European Walking Route E1 that crosses the whole continent – leading eventually to the Northern Apennines, and further down into Central and Southern Italy – while the Grand Italian Trail crosses the length of the range all the way to Calabria.

On a regional level, there are ‘shorter’ versions – such as the G.T.A. (“Grande Traversata Appenninica”) between Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany – plus innumerable thematic routes of a more local or historical interest. Worth mentioning among these – as far as the Northern Apennines are concerned – is the via Francigena, an ancient route walked by French pilgrims on their way to Rome.

The Bologna Apennines

And now – as I finish – allow me to become personal for a moment. The area of the Apennines that I know best is that around Bologna, as I was born there. I have therefore described some of the natural features around the regional capital of Emilia-Romagna in a bit more detail. There are, in fact, a few reserves which are worth mentioning in this section of the Northern Apennines – such as the Historic Park of Monte Sole (Parco Storico di Monte Sole) and the Regional Park of the Pliocenic Rampart (Parco Regionale del Contrafforte Pliocenico).

Other notable areas where to walk in this part of the Northern Apennines include sections at its foothills, such as the Gessi Bolognesi (Parco Regionale dei Gessi Bolognesi e Calanchi dell’Abbadessa) – a remarkable area for its geology and karstic phenomena – while further east into Romagna is the Regional Park of the Vena del Gesso (Parco Regionale della Vena del Gesso Romagnola); both these areas are renowned for their extensive chalk formations.

Also – even though this strays off a bit from the main topic of this page – not far from the hilltop town of Loiano (near Bologna) are the fascinating small gardens of the Casoncello (the picture above shows the wide, open expanse of the Northern Apennines from the area of the Gessi Bolognesi, very close to Bologna).

Return from Northern Apennines to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2019 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.