- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

The Po Delta: a Land where Sea and Fresh Water Meet -- a Haven for Bird-life.

The Po: a River with an Insidious Charm

The Po Delta is an area of outstanding natural beauty at the mouth of Italy’s longest river – and, funnily enough, the one with the shortest name too. The Po reaches the Adriatic sea after a peculiar course: just a tiny amount of its length is among the Alps, where its springs are (at the foot of Monviso, 3.841 m, the highest peak of the Cottian Alps); then, most of its long life is spent meandering in the middle of the Po plains – Italy’s largest expanse of flat lands, and its most densely inhabited area. But it all changes as soon as the river starts to approach the sea, where the plains become more and more devoid of human presence, and a sense of emptiness starts to prevail (above, see an atmospheric image of the Po embankments – abundantly covered with red poppies – near Ferrara).

The Po then expires quietly, having enjoyed its short-lived youthful exuberance while tumbling through the Alps. Venerable in old age, it fans out into a Delta worthy of the greatest rivers, forming a river-lagoon habitat with a curiously powerful appeal even to those whose first love is not bird-watching. This unusual wilderness embraces dunes, swamp, freshwater marsh and strange formless areas of shifting sands, islands and mud-flats in between, covering thousands of hectares. Landscapes are flat and ethereal; skies huge. Lonely horizons stretch across mist-patched or shimmering sheets of water; in addition, winter brings the chilly desolation of windswept sands and grey-scudding seas.

This silent and remote land where fresh and salt water meet is one of the most important wetlands for shore-birds and migrating waders in the Mediterranean (although here, strictly speaking, we are along the Adriatic coast, this area can still be considered part of the Mediterranean region).

In this eerie flat land, vast areas of marshland were drained for farming, starting in the late 19th century and continuing right through into the 1960s. Drilling for natural gas, also, proceeded unchecked for a long time, while the commercial extraction of sand and gravel caused subsidence and added to the already high risk of flooding along the river banks. As a matter of fact, the Po often floods the area along its embankments, especially in the stretch between Ferrara and the sea (as in the picture above): these temporary wetlands also become important shelters for bird-life, and the aesthetic result can be quite haunting at times, despite the industrial presence (see for instance the image below). On top of this, in the early 1980s a power station was plonked down right in the middle of the Delta, despite widespread protest. As if this were not enough, industrial and agricultural effluent had by then turned the Po into one of Europe’s most polluted rivers. It took the growth of huge banks of algae in the Adriatic sea – nurtured by the Po’s contaminated discharge – to force the authorities to finally do something about it.

The Po Delta Regional Park

Luckily, gone are the times when this outstanding area was not protected by proper environmental safeguards: at long last, in 1988 Emilia-Romagna declared the birth of the Po Delta Regional Park, covering the southern margins of the region and a long section of littoral, dunes and marshes culminating in the salt-flats at Cervia, south of Ravenna. The majority of the Delta, which falls on the Veneto side of the regional border, though, remained unprotected until 1997, when it was finally included too within a Regional Park bearing the same name. Eventually, from the original 6,000 ha of reserves, today the two Regional Parks together cover an area in excess of 70,000 ha – and that is a huge area to roam!

Plans are even afoot to extend the protection up as far as Chioggia, on the southern tip of the Venetian lagoon, and to turn the whole area into an inter-regional park managed jointly by Veneto and Emilia-Romagna; for now, however, the two regions are running their sections independently – but they have at least made a start on cleaning up the pollution and halting encroachment by agricultural practices and industry.

The Po: a Textbook Delta

The Po is a textbook Delta, created in a region with the most perfect preconditions for Delta formation. The Adriatic is like a long sheltered gulf fed by a sea virtually free of tides and currents; anywhere else, the river’s silt might have been dispersed, but here it has settled undisturbed at its mouth. Numerous tributaries add enormous volumes of silt eroded from their upper reaches: the Po is estimated to deposit a ton of silt for every thousand tons of flowing water. Three other large rivers – the Adige, Brenta (to the north) and Reno (to the south) – also empty into the sea nearby, adding their silt to the coastal waters.

Such is the scale of deposition that following the Po to its mouth becomes a difficult task. Having drifted and weaved through different courses over the centuries, the river has formed a leaf-skeleton of streams and channels – creating land one year, removing it the next. As it meanders seaward, east of Ferrara the Po loses its identity to such an extent that it is rechristened as a series of branches: the Po di Levante, the Po di Venezia, the Po della Pila, the Po di Gnocca, the Po di Goro – and so forth.

Thousands of birds pass through here on their migration route, spending the winter among the Po Delta lagoons and marshes. They are especially drawn to the Valli di Comacchio – so called ‘valleys’, but ranging from sea-linked lakes to deep still pools rich in aquatic activity, lined by solitary poplars and threaded by small canals. Until 1152 – when the Po broke away from its original course with the disastrous “Rotta di Ficarolo” – this used to be the Delta; now the river struggles seaward to the north.

The ‘valli’ were formed as the sea retreated during the Middle Ages, and were much reduced by drainage projects after WW2; what survives, though, is a paradise for waterfowl. Most noticeable are the thousand or so gray-lag geese, easily identifiable by their yellowish legs and bills. Up to 10,000 coot congregate here during the winter, when wood-, common- and green sandpiper – as well as dunlin – can also be seen. Pygmy cormorant number 3,000 to 4,000, while knot and sanderling, although present, are harder to spot.

Breeding birds are found in smaller numbers, but what they lack in quantity they make up in sheer variety. The islands in the Po Delta support large colonies of herons, which nest along the banks of the Po di Maestra and more inland at Campotto (see picture below). The brackish lagoons at Valle Bertuzzi, Lago delle Nazioni and Foce del Po di Volano have large numbers of Mediterranean- and black-headed gulls, wintering diving ducks – such as tufted duck – as well as black-, sandwich- and gull-billed terns. Birds that had once vanished from Italy – such as the hen harrier – are reported to be returning; most remarkably, the greater flamingo has been nesting in the Valli di Comacchio since 2000.

The Ecomuseum of Argenta

The whole region around the Po Delta – even for quite some distance inland – is undoubtedly dominated by water, and very rich in canals too. In the area around Campotto and Argenta there is an interesting Ecomuseum, which aims to show the continued struggle for man to achieve a precarious balance with water in these plains, as well as conveying the naturalistic values that the incredible region of the Po Delta – certainly subdued, very often understated – can offer.

The Ecomuseum of Argenta is situated right at the centre of a triangle formed by the cities of Ferrara, Ravenna and Bologna, and can be quite easily reached from all three. It tells the environment, the history and the culture of this territory and its people, with a striking combination that comprises three different museums and a naturalistic section. On the whole, it expresses the character of this land and the of communities which inhabit it, while looking after its extraordinary heritage.

The Museo delle Valli – annexed to the nearby Nature Reserve at Campotto – documents the evolution of the natural environment and the intervention of man in an area traditionally dominated by water, while providing information on natural history; it is also one of the Visitor Centres for the Emilia-Romagna side of the park. The Museo della Bonifica is a unique example of industrial archaeology and is at the same time an active site; it tells the story of drainage projects in the area – as well as displaying pieces of machinery, sometimes still in use (the plant is in working order). A third museum is the Civic Museum: hosted in a former church in the centre of town, it is a good complement to the naturalistic collections as it displays a picture gallery and an archaeology section, both documenting the civic and artistic life of Argenta. More information on the two museums of naturalistic value is provided below; the Civic Museum is not described here in detail.

The Museo della Bonifica

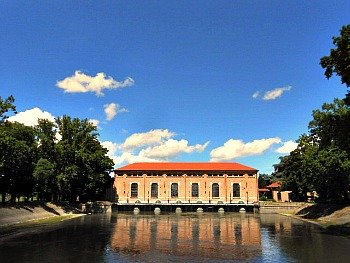

The Museo della Bonifica (Museum of the Reclaimed Lands) has its headquarters in the Stabilimento Idrovoro (water pumping station) at Saiarino – a monumental building that epitomises a common presence in these flat lands (there are many of these buildings, and visiting one of them would certainly help you to read the landscape with different, more educated eyes). The museum shows the general procedure of the reclamation process, as it was carried out traditionally; the artifacts, the pieces of machinery and their functioning are all well explained.

It is also a good example of industrial archaeology, where machines and the historic plant are integrated with the human and technical resources of the Consorzio della Bonifica Renana – the institution that historically has been in charge of reclamation in this delicate section of the Po Valley. The visit route is articulated both outdoors (see the image above) and indoors – as well as in the company buildings – and includes the emissary canal, the archaeological route (displaying dismissed pieces of machinery), the impressive, cathedral-like pumping room (pictured below) and the historic plant.

The Museo delle Valli

This museum is divided into a section dedicated to the Po Delta Regional Park (in the Emilia-Romagna side), a section focused on the historical-anthropological features of the area and a naturalistic section. Park Area: all the stations into which the park has been divided are presented with the help of images and descriptive panels. Historical-anthropological section: on the ground floor, this section offers the possibility to understand the evolution of this territory and the life of man within it. Naturalistic section: on the first floor, it displays an itinerary across the four main environments of the Campotto Nature Reserve nearby; that is: the hygrophilous forest, the wet meadows, the reed beds and the cat-tail (Typha latifolia) formation. A multi-sensory video with special effects leads the visitor into a virtual visit too (see an image of the museum's exterior below).

Campotto Nature Reserve

Connected to the museum are these lagoons – also called Valli di Argenta – which represent one of the foremost examples of fresh-water wetlands in continental Europe. These lands escaped reclamation thanks to their important hydraulic function, as they act as expansion basins for two of the river Reno's main tributaries (the Idice and Sillaro), holding their excess water when they are in flood. The territory is also crossed by a huge network of canals, which help regulating the flow of the water streams (see a picture of the reserve below).

Notable Natural Sites: the Boscone della Mesola

There were once great forests south of the Po Delta, on the coastal strip leading towards Ravenna; today, only a few remnants survive – including the important Mesola woodland (Boscone della Mesola), which with its red and fallow deer it hosts the oldest populations of these animals in peninsular Italy. Hares, hedgehogs and weasels also thrive in this wildlife sanctuary – the most important expanse of woodland along the stretch of Adriatic coast between Ravenna and Venice (in the picture below, the entrance to the Boscone -- Great Wood -- which is accessible to the public only on weekends and on selected days during the week. Notice the Venetian slab to the left, indicating that this area was once possession of the Republic of Venice).

The Castle of Mesola

This impressive expanse of woodland takes its name from the nearby town of Mesola, in which we find an impressive, turreted castle (see an image below). This important historic building now hosts the main visitor centre for the Emilia-Romagna section of the Po Delta Regional Park, together with further information on the history of the area – as well as the incredible story of how the river Po has changed its course many times over the centuries.

In the charming setting of the Castle you will find, on the second floor, the “Museum of the Woodland and the Deer of Mesola”. The exhibits illustrate, through cartographic documents, the evolution of the territory of Mesola and its most significant environmental features, including the Gran Bosco della Mesola and its “Deer of the Dunes”, also thanks to the elaboration of the latest scientific data under the supervision of the University of Ferrara. The visitor will discover a collection of copies from the Herbarium by Filippo De Pisis – the painter from Ferrara who in the early 20th century collected, classified and preserved plants coming from Mesola Woodland and adjacent areas, before giving them to the University of Padova, where they are still preserved. A section is dedicated to the Deer of Mesola: a particular animal for its genetic features, its physical aspect and its behavior; the exhibit summarizes its development, documenting it with the traces in the history and culture of Ferrara found in paleontological deposits; in prehistoric, Etruscan, and Roman settlements; in the Christian worship; in the Renaissance art and traditions of the Corte Estense in Ferrara. This Museum represents a homage to the territory of the Po Delta and an invitation to discover its rich history, culture, traditions, nature and tastes.

The Fossil Dunes at Massenzatica

Near Mesola is also another interesting Nature Reserve: the Dune Fossili di Massenzatica (fossil dunes). Although this is a very small site, it is extremely important and instrumental for understanding the history of the area, as it reveals a lot on the implications of the presence of a shifting river in terms of changes in the outline of the landscape (see a picture with the entrance to the reserve below).

The Abbazia di Pomposa

Traveling south, one soon encounters – isolated on the surrounding flat land – the majestic presence of Pomposa Abbey (Abbazia di Pomposa), one of the most important religious buildings in Northern Italy in Medieval times. Founded in the 9th century, at the time this was a powerful institution that owned lands, salt-flats and fishing valleys in the area, and contributed significantly to the maintenance of an otherwise very difficult balance – that between land and water: a task which was a lot more challenging to achieve in ancient times than it is now. This circumstance in fact decreed, in the end, the very decay of the religious compound, as the island on which it was originally built gradually filled up from the 12th century onwards, and – as a result – the monks of Pomposa slowly lost grip on the land they were so painstakingly working (see an image of Pomposa below).

As it can be appreciated from the picture, the Campanile (bell tower) of Pomposa – besides being an incredible architectural achievement in its own right – announces the presence of the abbey from many miles afar, and represents an indisputable landmark on an otherwise desperately flat landscape. Inside, the abbey church hosts several cycles of frescoes; overall, Pomposa can rightly be considered the most important monument within the Po Delta Regional Park (see an image of the church interior below).

The pinete in Ravenna

Proceeding further south, north and south of Ravenna respectively are also the pinete – or pine woods – of San Vitale and Classe. The conifers are thought to have been introduced by the Etruscans in Pre-Roman times, and were exploited by the Romans to provide timber for their fleet. Nature, left to its own devices, has since run riot: mature oak, ash and holly – intermingled with various species of maritime pine – rise above a lush forest floor. The beauty and tranquility of these woods, with their sun-dappled glades, have been praised by generations of poets – from Dante to Lord Byron.

Return from Po Delta to Emilia-Romagna

Return from Po Delta to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2013 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.