- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

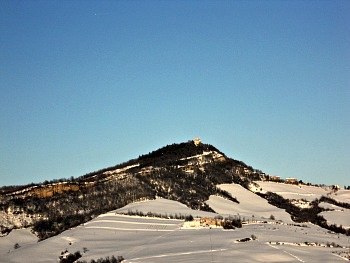

The Pliocenic Rampart in the Apennines of Bologna: Dramatic Rock Formation Commanding Vast Views.

The Pliocenic Rampart chain of sandy rocks rises along an internal line of foothills dating back to the Pliocene period, which stands out imposingly where the Reno and Setta rivers meet, then continues eastwards. This used to be the coastline of an ancient sea which once covered the present Pianura Padana (the Po valley plain). In its sandy rock faces, well known to climbers, Peregrine Falcons make their nest, while the surrounding area is full of historical treasures – such as the 'colombario': an ancient sepulchre carved deep into the rock cliffs

The Natural Regional Reserve of the Pliocenic Rampart (‘Contrafforte Pliocenico’) now protects a particular and majestic feature: a line of sandstone bastions which – in the Northern Apennines, south of Bologna – rises for about 15 km, transversely to the valleys of the river Reno and the Setta, Savena, Zena and Idice streams, from which stand out the stark line of mountains that include Monte Mario (466 m), the Rocca di Badolo (476 m; pictured above), Monte Adone (654 m) and Monte Rosso (591 m). The reserve – instituted in 2006 – is the last but also the vastest in Emilia-Romagna, as it extends over 750 ha. in the municipalities of Monzuno, Pianoro and Sasso Marconi.

The peculiar characteristics of this territory have given origin to diversified and contrasting environments, of noteworthy interest for their flora and fauna – to the point that the area represents a fundamental reserve of biologic diversity and it is entirely comprised within the Zone of Special Interest ‘Contrafforte Pliocenico’, protected at European level (thus also becoming part of the ecologic network ‘Nature 2000’).

To the extensive rocky outcrops facing SW, rich in marine fossils – that witnessed the origin of the sediments, which were deposited in a small marine gulf during the course of the Pliocene (between 5 and 2 million years ago) – are directly opposed the NE-facing slopes, softer and more accessible, on which grows a mixed broadleaved woodland; therefore, in the area live together plants of very different origin and distribution, as for instance Holm oak – which is typical of the Mediterranean vegetation – sits beside beech, which is more widespread in mountain woodlands found at higher altitudes. From the point of view of the fauna, the scarce human presence and the relative remoteness of the area (at least in some parts) have allowed the settling of some rare species of amphibians and birds.

The reserve is divided into three zones, which reflect a different range of uses and activities, compatible with the different parts of the territory and their degree of protection. Zone 1 identifies the most delicate section from the point of view of geology, vegetation and fauna; it includes the rocky outcrops and the areas of highest natural value, which necessitate the conservation of the area in its entirety. Zone 1/A – of very limited extension – individuates the two areas destined to rock-climbing (pictured below), an activity traditionally quite popular in the area, and which was not banned by the institution of the reserve. Zone 2 identifies areas which are destined to the conservation of environmental quality and are dedicated to a continual experimentation: striking a balance between human presence and the natural environment; in this area are therefore allowed some activities such as the collection of truffles – obviously not freely, but with modalities which are regulated by law.

Visit to the Reserve

The visit to the Pliocenic Rampart can be done freely at any time of the year, but uniquely along the network of paths which have been officially recognized and marked, as well as by using the country lanes that depart from the main hamlets (there are no major towns within the area). Traveling on foot constitutes one of the best ways to get to know and appreciate the reserve and its habitats, from woodland to meadows; from the rocky outcrops to the water courses. All the paths that can be walked are marked and numbered with the traditional red-and-white strips of the Italian Touring Club (CAI).

A great help to the trekker is that each sign reports on the higher part the name of the first locality that will be encountered along the way, while on the lower part is indicated the terminus of the path; the possible acronyms on the arrow indicate that that stretch of path coincides with the section of a longer itinerary (long-distance path) that also crosses the territory of the reserve. So the following acronyms can be encountered: T5V, VD and VS, which indicate respectively: the “Traversata delle Cinque Valli” (Traverse of the Five Valleys – that is, the valleys of the Reno, Setta, Savena, Zena and Idice), the “Via degli Dei” ('The Way of the Gods', also marked sometimes with two yellow dots) and the “Via dei Santuari” (The Way of the Sanctuaries).

The first one connects Monteveglio with Ozzano dell’Emilia and is developed along hilly streets, country lanes and paths crossing longitudinally a good deal of the reserve; the second is an itinerary that doubles part of an ancient link between Bologna and Florence and crosses the reserve for about half of its length (in the section from Sasso Marconi to the hamlet of Brento); the third indicates a long-distance trekking route that was created in the occasion of the Jubilee of 2000, which connects Bologna to Prato while linking some of the most important religious buildings in this part of the Northern Apennines, and touches on some of its most fascinating locations.

Noteworthy Locations in the Reserve

The most beautiful sites within the reserve include Monte Mario (466 m), the Rocca di Badolo (476 m), Monte Adone (654 m) and Monte Rosso (591 m). The first two are easily reachable from Sasso Marconi; the second in particular is an interesting destination as it is an ancient sacred site, where a place of worship has been located for centuries; unfortunately, today there is only an ugly chapel at the top (pictured above; notice the rocky outcrop just behind it), but the path to get there is still very atmospheric, carved as it is among sandstone walls (see the image below).

Monte Adone (pictured below) is a huge, long sandstone bastion with several rocky outcrops peppered with caves and also a sacred air to it; it is covered by an extensive network of paths that climb the mountain from several locations. It is located roughly at the heart of the reserve and represents its highest point too.

Finally, Monte Rosso can be accessed from the hamlet of Livergnano and it also displays similar characteristics, but is perhaps less distinctive than the other locations. This stretch is perhaps more striking when viewed from a distance, such as in the picture below (for more information on this section, see Bologna Apennines).

The Monte delle Formiche

The ridge then continues beyond the Zena valley, where the Pliocenic Rampart lies outside the boundaries of the Nature Reserve and reaches another notable peak: Monte delle Formiche, 624 m – literally the Ant’s Mountain, where storms of flying ants go there to die every year in September (see a winter image of the mountain below). This unusual event, which was never fully explained, has always called traditional pilgrimages to this holy mountain throughout the centuries (hermits even lived here); from the ants was once also derived an ointment which was reputed to have miraculous properties, and that in popular belief could cure many ailments.

It is also worth pointing out that most of the lower sections of the valleys that cut through the Bologna Apennines (especially on the eastern side – Savena, Zena, Idice) have gorges that were deeply carved into the soft sandstone layers forming the base of the Pliocenic Rampart (see for instance the picture below). Sandstone is by far the dominant type of rock in this section of the Apennines, and it gives a predominantly yellowish tinge to the landscape here.

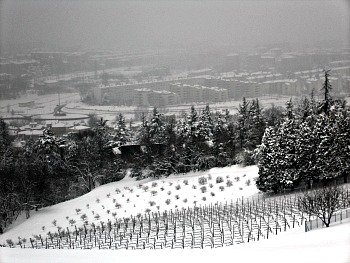

Having said that, in stark contrast with the ruggedness of the Pliocenic Rampart, the landscapes which can be enjoyed when walking over its main ridge or while ascending its peaks are mostly soft and gentle, as they open up over fields that are generally cultivated with wheat or fodder over the summer, and therefore very verdant. In winter these turn into wide – and white – expanses punctuated by solitary trees, as in the image below.

Further beyond, especially on clear days, the views can reach as far as the main summits of the Northern Apennines (as seen from the image below, with the highest peak – Monte Cimone, 2,165 m – right in the middle of the picture).

As a final word of warning, when walking in the Pliocenic Rampart reserve, be warned that sometimes fences and/or specific signs may restrict the access to some of the paths, which can temporarily be closed off either for some danger or as they cross areas that are particularly delicate from the point of view of conservation at that given time.

Return from Pliocenic Rampart to Northern Apennines

Return from Pliocenic Rampart to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2013 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.