- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

Agordo and its Region – in the ‘Kingdom of the Owl’: the ‘Dolomite face’ of Mount Civetta.

The Lower Cordévole Valley

Agordo and its territory correspond to the southernmost and westernmost sections of the Dolomites within the province of Belluno.

The main axis of this sub-region is the river Cordévole, which in its lower reaches crosses the area protected by the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park.

Its lower course is almost carved between the high rock walls of Monte Schiara (2,563 m) on one side, and the wild Monti del Sole (2,240 m) on the other.

This stretch of the Val Cordevole is like a long canyon, known as Canale d’Agordo and very little inhabited – apart from the presence of small hamlets often developed around facilities for pilgrims: the so-called “postal stations” (“stazioni di posta”), inns once used by the postal services, where horses could be rested and fed, and restoration provided along busy thoroughfares.

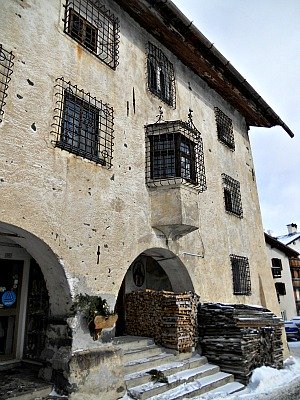

Such is the case for example of La Stanga and Candàten, where there is one such beautiful specimen of traditional architecture (now reconverted and used by the Italian Forestry Commission for their administrative headquarters; first picture above).

From Candàten, as you cross the Cordévole, you can also follow the Zanardo Nature Trail, while it is particularly charming is to walk along the right bank of the river, on the section of the “Via degli Ospizi” (the ‘Pilgrim’s Way’) between San Gottardo and Salét.

On the left side of the river, there are instead small tributaries forming fascinating ravines, gorges, and potholes – such as those in Val di Piero, Val Ru de Molin, Val Vescovà and Val Clusa.

Near the farmsteads at Agre – that follow up along the main road – there have been important archeological finds.

The hamlet of Agre lies at the entrance of the fascinating Val Pegolèra, the largest and most emblematic valley of the Monti del Sole – the so-called “Mountains of the Sun”, where the park gets “wild at heart”.

Paths ascending on the surrounding slopes from here are hard and steep. The most accessible valley – through a forest road – is the Val Vescovà, rich in beautiful woods.

This valley is a gateway to Rifugio Bianchet, a mountain hut located at Pian dei Gatt (1,245 m). From there, you can then ascend to Forcella La Varetta and on to the southern slopes of Monte Tàlvena (2, 542 m; part of the Schiara group), across an area extraordinarily rich in flora, matched in this respect only by the Vette Feltrine.

The Valle Imperina

As the valley opens up slightly, a group of impressive buildings come into sight on the other side of the river: this is Valle Imperina (pictured above), once an important mining settlement, centre of the copper extraction industry, which influenced for many years the economy of the Agordo area.

Seemingly used since Roman times, the first official document is dated 1160; in Venetian time, the site quickly became the most important copper mine in the Republic of Venice. The kilns were closed in 1898, but production of sulphuric acid carried on until as late as 1962.

At that point, the whole site was abandoned for a long time, and only recently it was reconverted by the Park authority into a multi-functional compound. At its maximum expansion, Valle Imperina comprised 16 buildings; some of them have disappeared, but others have been restored, so that now the area hosts one of the Park's main Visitor Centres, a youth hostel, a restaurant, a space for meetings and a museum.

The exhibitions especially provide the most astonishing insights on this place, as the serene setting of today – with its extensive tree cover on the mountainsides – is deceiving of its history.

In stark contrast, powerful and almost frightening images reveal a landscape until not so long ago scorched and damaged by the copper oxides and the fumes exuding from the mines, which decimated the trees and polluted the river, making the people sick (see, in the picture below, an image of the oxidised water at the mining site of Valle Imperina).

This is a poignant reminder of what man can do – once like today – to its environment and to himself, and provides good food for thought.

But it is not all doom and gloom, by all means: there is also an interesting section on local history, myths and traditions, and some of the stories told here are really fascinating, sinking deep into the pre-Christian and Pagan layers – such as those on the “Green Man” and the “Mazariòl” (a red-capped, small playful creature said to inhabit these mountains, and who takes amusement in causing walkers to lose their bearings).

Some interesting walking itineraries also start from the Valle Imperina: the path once used by the miners takes one further to more industrial remains dug into the mountainside; continuing, it leads eventually to Casèra Mandre through a beautiful beech wood interspersed with spruce.

Another path leads to Pianaz instead and – at higher altitudes and along more difficult trails – across the Val Frescat to Bus de le Nèole, which is a unique morphological phenomenon.

As a matter of fact, the Valle Imperina is a good reminder of the fact that Agordo and its territory – as well as neighbouring Zoldano – differ substantially from the remaining mountainous section of the province of Belluno.

Historically, these two sub-regions have always gravitated on to the provincial capital, and followed it when in 1404 Belluno became part of the Venetian Republic.

That is when the exploitation of natural (especially mineral) resources reached its peak – and this fact would shape the landscape for a few centuries to come, when Agordo and Zoldo became in fact known mainly as mining districts.

Agordo, Small “Capital” of the Area

After the Valle Imperina, one reaches Agordo itself – a small town which can be considered the main historic and administrative centre for the whole Agordino area, where several side-valleys meet.

At the centre of an open basin dominated by Monte Agnér (2,871 m) and Framont (2,293 m), Agordo developed as a market town, where all the raw materials coming from the surrounding mines would converge before continuing their journey southwards (traditional uses for the iron mined in the Agordo region included the forging of swords in Belluno, or its use for the mint in Venice).

The main square in Agordo still retains traces of the prosperity that this trade brought with it: the Palazzo Crotta-De Manzoni is a typical 18th century villa – its balustrades are lined with traditional rows of statues, in Venetian style, representing fifteen pagan deities.

The massive church of Santa Maria Nascente, erected by Giuseppe Segusini (a very active architect in the area in the 19th century – see, for instance, Auronzo), is a landmark for the whole Agordo basin, and it hosts paintings by Palma il Giovane, while the wide main square, occupied in the middle by an open field and known as “El Broi” (from the Latin Broleus), was traditionally used as a market space.

In keeping with the trading tradition of Agordo, the arcaded side of the square lined by elegant buildings is still brimming today with cafés and shops.

The Valley of San Lucano and Rifugio Vazzolèr

Past Agordo, the landscape widens and takes up connotations more typical of the Dolomites. From the next village of Taibòn Agordino, a side valley to the left (when travelling northwards) leads into the beautifully untamed Valley of San Lucano, deeply cut under the almost intimidating walls of the Pale di San Lucano (2,409 m; pictured above) and of Monte Agnér (2,871 m).

The road terminates at Col di Prà (pictured below), a serene hamlet at the head of the valley, dominated by the picturesque sight of the outlying ranges of the Pale di San Martino (2,939 m), with the highest peak (Cimon della Pala, 3,192 m) visible in the background. This is also the location from where all paths leading up to higher ground start.

Going back to the main valley floor, on the other side of the val Cordevole (right-hand side, when travelling north), another side valley opens up by the village of Listolade.

A tarmac road leads first to Rifugio Capanna Trieste (1,135 m), where cars can be left, after which the road turns into a mule-track that winds up the mountain side, with hairpin bends offering impressive views over the Civetta (“the Owl”) – at 3,220 m one of the most astounding massifs in the Dolomites.

Cima Busazza (2,891 m) is also visible form here, but the landscape is dominated by the overhanging rock towers of Torre Trieste – whose overbearing ‘head’ looks like a sphinx – and Torre Venezia.

Here, near Rifugio

Vazzoler (1,714 m), a small

but pretty Alpine botanic garden (“Giardino Botanico Alpino Antonio Segni”) can

be found, dedicated to high-altitude plants left to grow in their natural

setting, and accurately signposted. The garden is described in more detail just below.

The Antonio Segni Alpine Botanical Garden

The Alpine Garden dedicated to the historic President of the Italian Alpine Club organization (CAI), Antonio Segni, was born out of the desire of the Conegliano section of the CAI, and was inaugurated in June 1968. The garden extends on an overall surface of 5,000 sq m; it includes an area left to natural evolution, and a section characterized by rockeries created with layer detritus, using sedimentary rocks typical of the Civetta group. If you enter the garden, you will realize that in the beds not everything is in perfect order… as this is a garden open only during the summer months and looked after by volunteers. But despite that, this allows for a more natural feel. Take some time to observe the plants, and imagine taking a route along a trail that will take you from the valleys covered in woodland to the Alpine pastures, to then arrive at the scree – and even higher, up to the rocky crags. And with a bit of spirit of observation, you will notice how nature has taught plants to adapt to the different mountain environments.

The Flora and Vegetation

The Garden is set in a landscape context in which it is possible to notice how the different aspects of vegetation gradually fade from woodland tree formations into shrub formations, until the Alpine pastures and the meadow uplands, to end with the colonization of the screes present at the base of the vertical rock walls.

The Conifer Woodland. The woodland present in the Sub-Alpine spruce forest type is dominated by Norway Spruce (Picea abies), to which is associated – in a secondary way – Larch (Larix decidua), the only conifer in our climate to lose its needles during the autumn (when the plant becomes a beautiful golden color). To these, must be added some other tree and shrubs such as Beech (Fagus sylvatica), Alpine Laburnum (Laburnum alpinum), Sorbus sp. (Sorbus aucuparia and S. aria), Birch (Betula sp.) and numerous species of Willow (Salix sp.). In the undergrowth, mainly composed of Rhododendrons (Rhododendron ferrugineum and R. hirsutum) and Blueberries (Vaccinium myrtillus and V. vitis-idaea), are associated – in function of the different ecological factors – Juniper (Juniperus communis) and Honeysuckle (Lonicea xylosteum), or different species of Willow (Salix sp.) and Rose (Rosa sp.). In the undergrowth, amongst the branches, it is not rare to spot the climbing Alpine Clematis (Clematis alpina). In the woodland clearings are characteristic the splendid blossoms of Rosebay Willowherb (Chamerion angustifolium) and the rare Yellow Lady’s Slipper Orchid (Cypripedium calceolus).

The Contorted Shrubs. Above the tree line develops the band with the contorted shrubs, so-called for their prostrate, crawling habit of growth, with elastic branches, thanks to which they carry out an important function in consolidating the slopes, by preventing the onset of landslides and avalanches. This typology of vegetation is constituted – in function of the aspect (exposition), the soil type, the micro-climate and the other characteristics of a given location – by Dwarf Mountain Pine (Pinus mugo), Rhododendrons (Rhododendron ferrugineum and R. hirsutum), Juniper (Juniperus communis) and Green Alder (Alnus viridis).

The Rocky Habitats. The rocky habitats constitute areas in which it is very difficult for plants to thrive, because of the extreme conditions in which these environmental characteristics are being manifested. Drought, low temperatures, high sunlight levels, lack of soil and the exposition to high winds make these areas highly inhospitable, and require specific adaptations to the plants.

The Flora of the Scree. Plants like Bellflower (Campanula sp.), Mountain Avens (Dryas octopetala) and Alpine Gypsophila (Gypsophila repens) colonise the detritus amassed at the base of the scree – a typical element in the landscape of the Dolomites. The calcareous nature of these mountains exposes the rock masses to a continuous process of disintegration. The movement of detritus has led the pioneer species of the scree to develop large root systems, able to strongly anchor the plant to the substrate, while the capacity to activate dormant buds, able to generate new shoots, constitutes a useful mechanism in order to contrast the constant fall of stones from above and the covering – or breaking-up – of the aerial parts of the plants.

The Flora of the Rocks. The Alpine flora that colonises the rock masses is able to take advantage of the anchoring provided by powerful root apparatuses, which develop inside the crevices present on the rock walls. Inside these cracks, small quantities of clay and humus can accumulate, and roots can develop by following the shape of the fissure, reaching even some meters of length, driven by the goal of accessing the water that flows in the depths. Some of these species can develop a cushion-like shape – such as the Sandwort Minuartia sedoides and the Cinquefoil Potentilla nitida – or a rosette-like shape: that is the case of the Alpine Saxifrages, such as Saxifraga crustata and S. paniculata.

Places of Geological Interest around Cencenighe: Monte Anime

Geosite No. 1: the Palaeo-Riverbed of Monte Anime and Its Stratified Layers. This marks the tracks of an ancient riverbed (dating to around 245 million years ago), formed by the erosion of pre-existing rocks, following the emersion of these latter from the sea bed. In this specific instance, some deposits left by the river are also visible, formed by pebbles, gravel and boulders, with the conservation of one of the eroded banks of an ancient riverbed. The name of the rock that forms the palaeo-riverbed is Richthofen conglomerate (described below); the age is the Anisic (245-237 million years ago) and the period Triassic. Origin: sedimentation of pebbles, gravel and boulders, from a stream of moderate length, which carved its bed in the underlying bedrock, belonging to the Werfen formation (also described below), in a continental environment. In the conglomerate, the chaotic structure is evident: not very altered, non-specific, which testifies to the transportation of material during violent and sudden floods, in a semi-arid environment and climate. Eroded rocks: these are sandstones, silts and a marly calcareous stone, previously deposited in a shallow marine environment and belonging to the Cencenighe Member; that is, to the upper part (Olenkian) of the Werfen formation (249-245 million years ago), following the temporary emersion of this area from the sea (as for most of the remaining Dolomites). In the conglomerate one can find, sometimes, pebbles dating to the more ancient Bellerophon formation, which belongs to the Upper Permian. This documents that, during the Anisic, in the surrounding area took place the emersion from the sea of the whole Werfen formation, which was later completely eroded, until revealing the underlying Permian formation (area of Colfosco, Val Badia, etc.). The layers: the Richthofen conglomerate lays in clear discordance above the Werfen formation. It is covered, almost like a ‘roof’, by the formations known as Morbiach Limestone (regularly layered and perfectly visible upstream) and Contrin formation (or Serlia Dolomite; both are described below), which forms the well-known rock face of Monte Anime, which was affected by a massive landslide on May, 23, 1940 (a harbinger of ominous events to come, some said, as Italy entered WW2 on June 10). References: in other locations, other types of conglomerate, which were formed by similar phenomena of marine emersion and subsequent erosion, take the name of Voltago Conglomerate (from the name of a nearby locality), Piz da Peres Conglomerate (from the name of a mountain in the area), Tretto Conglomerate, etc. They are part of the so-called “Braies group”, a complex set of various sedimentary formations, all dating to the Anisic age.

Geosite No. 2: Crossed Stratification (Layering). This represents an anomaly in the sedimentation, which normally takes place in parallel layers, but in this case shows layers which are variably crossed, discordant between themselves and with those above and below. Origin: sedimentation in a delta, or littoral (coast) environment. It documents an ancient river that has carried its fine sediments (sand, silt, clay ...) to the sea. In the proceedings of the sedimentation, levels of discontinued and crossed stratification sometimes were formed, which indicate the advancement of the deposits towards the open sea, with frequent modifications in the direction of the fluvial currents. Each small layer corresponds to a single sedimentary event, connected to a river flooding. Stratigraphic reference: here we find fine sandstone, silts and marly calcareous rocks, of purple-red colour (which testify to the marine environment, with phenomena of oxidation in shallow waters), belonging to the Cencenighe Member, which constitutes the upper part (Olenkian; Scitic plane) of the Werfen formation (Lower Trias; circa 249-245 million years ago), and takes its name from the nearby town of Cencenighe.

The Geological Context. Geosites Nos. 1 and 2, described above, can be contextualised within a limited sector of particular interest (see board on site). The geological sequence, from bottom to top, is the following:

– Werfen Formation (Scitic plane; Olenkian/Induan): this is a complex series of marly limestones (calcareous rocks), oolitic limestone, sandstone, micaceous silts, with a little of evaporitic Dolomite too, characterised by a fine layering, a few centimeters thick, of various colours but predominantly reddish. Frequent are the markings known as “ripple marks”, which testify to the deposition of a sandy littoral, ‘slumpings’ (submarine landslides) and the markings known as “ball and pillow structures”, as well as cross-stratification (especially in Geosite No. 2). The overall thickness, here, reaches (and sometimes is superior to) 250 meters. The Werfen Formation is subdivided into nine litho-stratigraphic units: the Tesero Horizon, the Mazzin Member, the Andraz Horizon, the Siusi Member, the Oolite with Gasteropods, the Campil Member, the Val Badia Member, the Cencenighe Member, the San Lucano Member (the latter is absent from this specific site as it has been eroded). The Werfen Formation here is limited, at the top layer, by the Richthofen Conglomerate, because of a discordance for lack of erosion. Most of these formations take their name from locations within the Dolomites: some of them are described in more detail below; if you are interested in a more detailed explanation or a full list of these rock formations, please refer to the dedicated page on the geology of the Dolomites.

– Richthofen Conglomerate (Lower Anisic): this is an Anisic formation, which testifies to an erosive activity which incised the underlying sediments, leaving more or less wide gaps in the stratigraphic series. It is constituted by one or more conglomerate banks, often separated and accompanied by grey or reddish silts, marly limestones, occasionally with carbon inserts. The thickness of the layers is very variable, from 0 to about 50 metres.

– Dark Morbiach Limestones (Middle-Upper Anisic): these are constituted by sandstone, grey sandy limestones, bituminous limestones and dark marly limestones, regularly stratified in layers about 10 cm thick, deposited in a shallow marine environment, often lacking in oxygen (which gives the typically predominant dark colour). The thickness reaches (and is often more than) 50 meters.

– Contrin Formation (aka Serla Dolomite; Middle-Upper Anisic). This is a very potent rock bank, about 100 meters thick, of organogenic nature, and a calcareous-dolomite composition. The rock is generally constituted by a type of Dolomite which is composed of micro-granules of saccharoid nature, white or greyish, porous, almost invariably rather massive, sometimes roughly stratified, and with frequent algae remains. This formation was originated by uniform deposits of fragments of algae, enveloped by silts of calcareous-dolomite nature.

Tectonics. The area is characterised by the so-called Anime fault-line, a great fracture which caused a movement, raising the South-eastern sector of this mountain of about 100 meters, thus taking the Richthofen conglomerate to resurface just upstream of the hamlet of Balestier. This fault-line is now largely hidden under the great landslide, with large Dolomite boulders, which on May, 23rd, 1940, interrupted the road to the Biois valley; an event following which the short Galleria delle Anime (road tunnel) was dug (now substituted by a longer and more functional tunnel). The markings, which point to the area where a large portion of Contrin Formation detached itself when the landslide occurred, is still visible from the nearby town of Cencenighe, and it is still affected by long, decompressing fissures, which are constantly being monitored, as they could be the cause of future rock collapses and subsequent landslides. All these layers are tilted about 15°/20° towards the SE.

The Upper Cordévole Valley (Alto

Agordino)

Back again to the main valley floor, the next village upstream is Cencenighe Agordino, a small resort at the confluence of the two rivers that form the Alto Agordino area (“Upper Agordino”), comprising the valleys of the Cordévole and its main tributary – the Biois.

This latter valley takes one eventually to the winter resort of Falcade and on to Trentino. Cencenighe was also a mining town, and an important intermediate station for the timber industry; the upper part of the village still retains some old, vernacular houses.

The river Cordévole is the central axis for the region centered on Agordo, which eventually leads on to the magnificent Val Fiorentina.

But before that, the National road takes one to Alleghe, an important resort that developed along the banks of a picturesque lake, formed in 1771 following a dramatic landslide. From here, there are celebrated, majestic views over the Civetta (3,220 m).

The village still hosts some old houses with the typical external circular fireplace (foghér) – a traditional feature of the Agordo region.

A short distance after Alleghe – and running under the impressive, precipitating northern face of Monte Civetta – the National road reaches Caprile, which lies at the confluence of the Fiorentina and Pettorina valleys.

In the old times, Caprile was also an important mining centre, and signs of its affluent past are reflected in a number of ancient houses – their noble standing indicated by their being built in stone as opposed to wood (which was used for the more humble dwellings of the populace) – and by the presence of a St. Mark's column in the main square, indicating the historic presence of Venice.

The Val Fiorentina

From Caprile, three different options open up: the first is to continue further up the Val Fiorentina until one gets to Selva di Cadore – which belongs to a part of Cadore known as ‘Oltremonti’, as it lies beyond the Boite watershed (this part is dealt together with the rest of the Zoldano).

The Val Fiorentina derives its name from ‘Ferentina’ – another reference to the historic presence of iron mines (iron translates as ‘ferro’ in Italian), closed down as far back as 1753 (the most important mining hub, Monte Pore, was close by).

The landscape is dominated here by the summits of Monte Pelmo (3,168 m), the Croda da Lago (2,709 m) and Becco di Mezzodì (2,603 m) – all peaks that show their best-known rock faces on the other side, over the Boite Valley and from Cortina d'Ampezzo.

Colle Santa Lucia

Just a few kilometers up the valley from Caprile into the Val Fiorentina is Colle Santa Lucia – a village whose architecture was visibly influenced by nearby Tyrol, as it belonged to the Austrian Empire up to 1923.

In this area, also known as “Ladinia Veneta”, the Ladin language is still spoken to this day, and Colle Santa Lucia displays a number of elegant buildings; most notably Casa Chizzali-Bonfadini (see image below), a 17th century house whose high standing is expressed not only by its being built in stone, but also by the traditional frescoes around the windows – Tyrolean style – as well as by the wrought-iron railings (another indication of the fact that iron was mined near here).

This house – as well as nearby Casa Piazza – displays a lower ground arcade, which indicates that it was inhabited by tradesmen. Today, the atmospheric interior of Casa Chizzali-Bonfadini can be visited, as it hosts the local Ladin culture centre as well as a small Ladin museum.

Many other interesting vernacular houses scattered around the village tend to be built in wood only, in line with the German tradition (see first image below).

The church (pictured in the second image below) is erected on the panoramic hill that lends the village its name, and has a fresco with St. Christopher on the main façade, while the style is Austrian rococo in the interior. From there, wide views open up on the whole Fiorentina valley.

While driving towards Colle Santa Lucia, do not forget to stop to admire the sights at the renowned ‘Belvedere’ (viewpoint), which affords magnificent views over the Cordévole valley and the vertiginous northern flank of Monte Civetta, which can be seen precipitating – from this angle – for more than a 1,000 m from the summit sheer to the valley floor.

By the ‘Belvedere’ is also a very nice restaurant which – besides the good local food – will also give you the opportunity to enter a lovingly restored typical building, with an abundance of wood and a welcoming ‘Stube’ to warm you up during the cold winter months.

The “Serrai di Sottoguda” and Towards the Marmolada

The second option from Caprile is to take the Pettorina valley instead, until one reaches Rocca Piètore, whose church contains a 15th century ‘Flügelaltar’ of German school, while only a few ruins remain of the once important Roccabruna castle.

Past this village, and as the valley gets narrower, it is advised to leave the main road and enter the village of Sottoguda, where the so-called “Serrai di Sottoguda” start.

This is an impressive deeply-cut gorge that the stream has carved into a natural canyon among precipitous walls – more than 2 km long and only 20 m wide – and which can only be accessed on foot.

At the exit of the gorge, the traditionally grazed fields of Malga Ciapela have been shamefully scarred by disproportionate buildings and other structures that have turned the area into a tourist resort dedicated mainly to winter sports.

Nevertheless, grandiose views open up on the Marmolada, with the two minor summits of Sasso di Valfredda (3,009 m) and Pizzo Serauta (3,069 m).

At 3,343 m, the Marmolada is the highest elevation in the Dolomites, and also the only mountain to host a permanent glacier of a certain relevance within the region.

Its highest peak is known as Punta Penìa – which means “nothing more” in the Ladin language, thus confirming the nature of this mountain as the ‘roof' of the Dolomites.

Past the Fedaia Pass (2,057 m) the National road enters Trentino, leading into the Val di Fassa and towards Canazei, in the Ladin-speaking Dolomites’ heartland (Ladinia).

The third and last option from Caprile would be to ascend further up to the very head of the Cordevole valley until entering the municipality of Livinallongo del Col di Lana – a beautiful high-Alpine area also known as Fodòm in Ladin, immersed in verdant pastures and surrounded by several Dolomites’ giants.

Return from Agordo to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2012 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.